Mystic, composer and physician, b. 1098 (Bermersheim, Germany), d. 17 September 1179 (Rupertsberg).

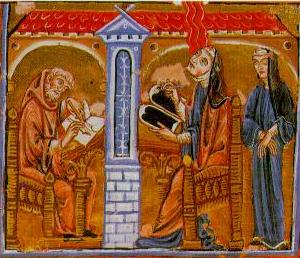

Hildegard von Bingen with Richardis von Stade (right) and Volmar (left).

miniature painting, c. 1230; Lucca, Biblioteca Statale

Hildegard von Bingen was born as the tenth and last child of a noble family, a position that usually meant life in a convent from an early age. The young Hildegard received a religious education away from her parents from the age of eight and entered the women's section of the cloister Disibodenberg when she turned fourteen. As a secluded nun she was locked in her cell and had contact with the outside world only through a small window.

Throughout her life Hildegard was of very unstable health and had long periods where she suffered from severe pain. She recalled in her autobiography that as a three year old child she already had visions, which she kept for herself when she noted that she was the only person to see them. In 1141, at the age "of 42 years and 7 months" a vision told her to write down what she had seen, and she began to write her first work, Scivias.

Writing often relieved her pain. In 1147 she confessed her writing to her priest, who had it assessed by pope Eugen III. The pope declared her a visionary and encouraged her to continue.

Medieval Europe had lost most of the Greek and Roman scientific tradition, but what was left of intellectual achievements was taught by monks in monasteries. Women were not allowed to study, and Hildegard's knowledge of the world came exclusively from her contact with other nuns during prayer and service. She knew Latin only from the regular recitals of the psalms, and her writing was rough and contained grammatical errors. The monk Volmar was assigned to her as a secretary to correct her text.

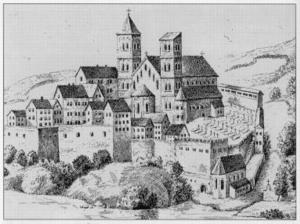

Hildegard's fame attracted more nuns to Disibodenberg than could be accommodated. A new convent was built at Rupertsberg near Bingen, and in 1150 Hildegard became the abbess of a self-supporting community that grew to 50 nuns and dozens of employees. She developed an intense relationship with the nun Richardis von Stade, the daughter of a noble family. When Richardis was appointed abbess of another convent Hildegard pleaded with the church authorities to send Richardis back to Rupertsberg but without success. From the tone of her letters it is evident that she desperately tried to save a love relationship.

Now well into her fifties, Hildegard became active in many areas and entered public life. She composed liturgical songs, which were soon taken up by monasteries in Germany and France. Her two works Physica and Causae et Curae contain 513 descriptions of plants, animals, elements and metals and discuss their medical and dietary uses. In letters to popes and bishops she castigated the clergy for amassing fortunes and neglecting their spiritual duties. She had harsh criticism for Frederick Barbarossa's attempts to curtail the power of the pope. At the age of 62 she went on her first extended trip to preach in monasteries and admonish the clergy around Germany. Three more trips followed, the last one when she was about 72.

During all these years Hildegard continued to write down her visions. She completed Liber vitae meritorum in 1163 and Liber divinorum operum in 1173. In all works she insisted that she never experienced a trance and always received her visions with a clear mind.

Many of Hildegard's visions were inspired descriptions of the medieval Christian view of the world. But they did not share its rejection of the human body as a depository of evil desire. Hildegard's philosophy stressed the unity of body and soul and the dependency of both on each other. Her description of the medical uses of plants and various foods in Physica and Causae et Curae is therefore more a guide to a healthy diet than a collection of cures for the sick.

The revolutionary character of Hildegard's vision showed particularly in the relationship between the sexes: "Man and woman are mingled in such a way that one is the work of the other." Because the soul needs the body just as the body needs the soul, it followed that love between man and woman has to be spiritual and physical: "The soul holds the all embracing love to its body, with whom she acts." For Hildegard, a discussion of physical love, including a description of the female orgasm, was a natural part of her guide to a healthy life.

Hildegard von Bingen was revered by the people already during her lifetime. Bishops and monks accepted her as an authority; even those who she castigated in her sermons asked for written copies for future study. But after her death the clergy soon tried to neutralize her and obstructed all efforts by the nuns of Rupertsberg to have her declared a saint. To this day she remains an "unofficial saint" and is remembered on the 17th of September.

The convent of Rupertsberg near Bingen on the Rhine during the 12th century.

Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin

Images: pubic domain